If you enjoy this post, please hit the heart button at the top or bottom of the screen. It helps others find this article. Thanks!

Lately I’ve been helping a number of people out with cash flow forecasts. Why this sudden spate? I have no idea. But it got me thinking there are probably more than just the few people asking me about it that have questions about it. Welp, I’m here to help.

Here’s the thing: “cash flow” is the underpinning of the language of capitalism. Regardless of how you might feel about it1, we live in a capitalist society that speaks its own distinct language. So, it’s pretty handy to know a few common phrases. Consider this the how to say “where’s the bathroom” in money-talk.

You might be wondering what any of this has to do with happiness. Honestly probably not a lot. But a part of being happy is understanding how the world works. This might not be as romantic as photosynthesis or as sexy as pheromones, but it is something that all of us use all the time yet don’t think about. We can consider it “mysterious” if nothing else.

PROFIT AND LOSS

Cash Flow Forecasts are built up and out from Profit and Loss (P&L) Statements. So we’re going to start there first. You are probably already aware of how Profit and Loss works. Even if you don’t, you do. If you have ever said (or even conceptualized) “I’ll sell it for $100, but it’ll cost me $75, so I’ll make $25,” then you have laid out a P&L (you’re smarter than you think). It looks like this:

That’s it. That’s a Profit and Loss statement. But it’s a little too… concise. One thing about the language of business is that it likes detail. Especially when it comes to costs2. In the P&L above we have one line: COST that we can break up into smaller, more meaningful parts. There are two types of costs:

Cost Of Goods Sold (COGS) - everything it will cost to build what we’re selling.

Expenses - all other costs that aren’t directly applied to making what we’re selling (think electricity, internet service, marketing, and the like).

Now the P&L will look like this:

Look at all that detail. That’s great! We can use that. But, you know something? We can go even further. COGS? That’s dumb. We can bust up COGS:

Labor - The amount of money spent on the human beings that actually work on building what we’re selling.

Material - The amount of money spent on the stuff from which the thing is made.

Now the P&L will look something like this:

Now we know all the costs that make up our costs. This is important and useful information. Yet, in the language of business and for the sake of more detail, we break profit up between how much we earn after building the thing we’re selling, and what we clear at the end. Why? Who knows?3 We just do. We end up with two sets of profits:

Gross Profit - What we earn after we’ve built what we’re selling.

Net Profit - What we keep after we’ve spent everything else we need to spend.

Now the P&L looks like this:

TADA! What you have here is a full on, honest to goodness Profit & Loss Statement. It’s beautiful (if you’re into that sort of thing). And that’s all there is to it - basically. Yes, it can get more complicated than that (much more), but this is the gist of it. With these numbers we can now build a cash flow forecast.

Prepare to be shocked and amazed!

THE CASH FLOW

Looking at Cash Flow is adding the time element to the Profit and Loss. We need to figure out when the money comes in and when the money goes out. We like to see how the cash flows through a business (get it? Cash floooOOoooow…). And, of course “forecast” is all about predicting what happens in the future. So this isn’t just a language lesson, it’s also about how to use a crystal ball4.

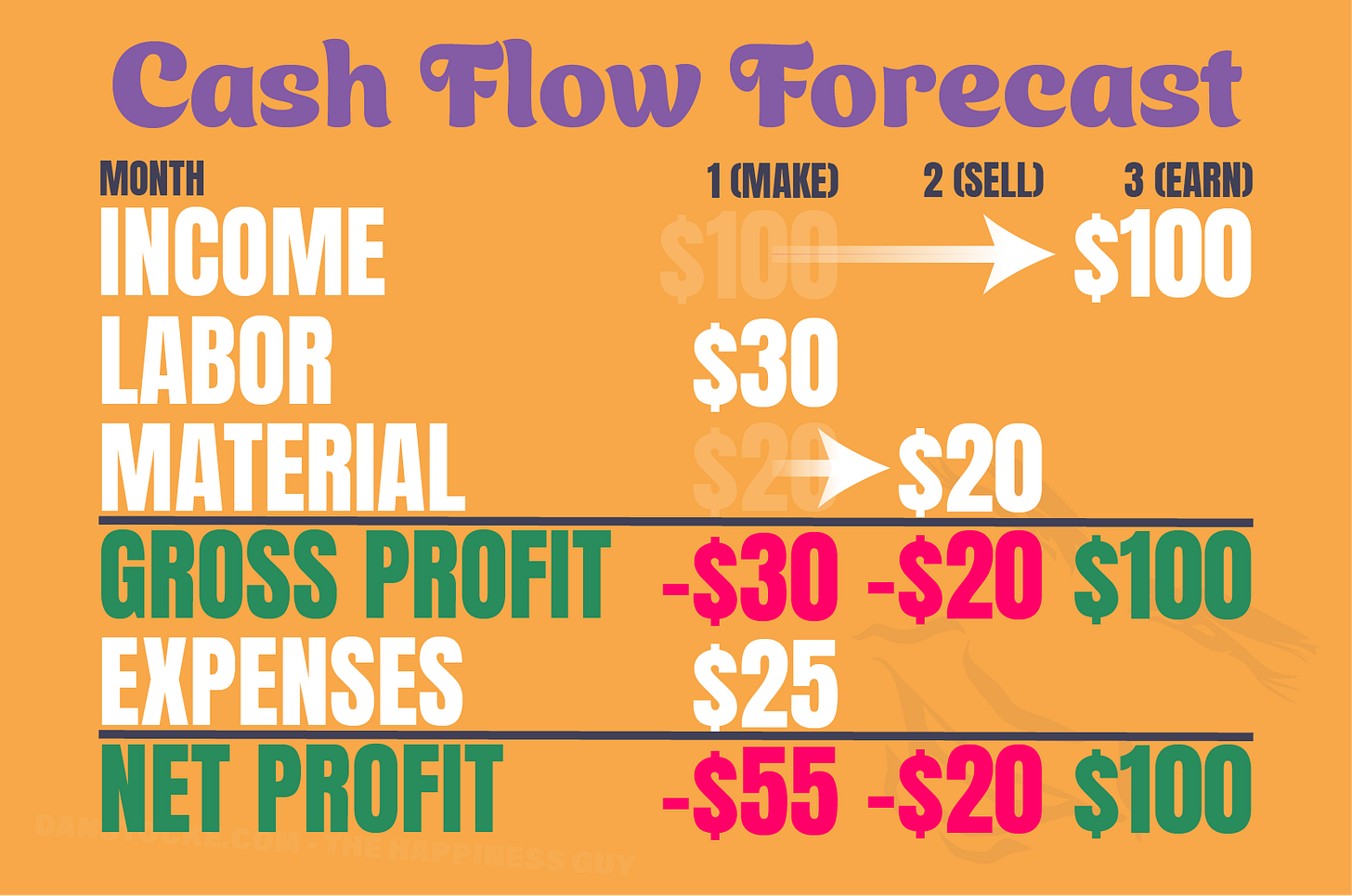

With a Cash Flow we take our Profit and Loss and break it into periods of time; it can be a weekly, monthly, quarterly, or yearly. Hell, it can be any timeframe you want - as long as it’s consistent. We’re going to bust our P&L into monthly chunks because… well, it’s typical. For now we are only going to look at the first three months. Why? Because that’s how long it takes (typically) for the cash to flow through it.

The whole point of business is to sell something. But you can’t sell anything until you make it. That means you have to spend money before you can make money5. The three months of cash flow are:

Make

Sell

Earn

1) THE MAKE MONTH

In the Make Month we’re going to build the thing we’re selling. The first thing we need to do is buy the material that we need to make the thing (wood, plastic, ice cream cones, or whatever). Luckily the person you buy that stuff from gives you 30 days to pay for it. WHAT?! That’s great! You get the stuff, but you don’t have to pay for it right away. How convenient.

Labor and expenses? Yeah, you have to pay that in the month you get it. You can’t tell an employee that just put in a hard 40 hours of work to wait 30 days to get paid. It won’t go well. Same thing with heat and electricity - there are repercussions if they don’t get paid. We should probably pay them right now.

2) THE SELL MONTH

After we have made the thing, we can go about selling it in the Sell Month. That happens in month number two. But, um, where’s our money? Why do we have to wait? Remember buying ice cream cones in month one and they were nice enough to give you 30 days to pay them back? Yeah, well, your customers now expect that same courtesy. Fine. We’ll give them a month to pay the bill.

Oh, also, the nice people who sold you the ice cream cones? They want their money now.

3) THE EARN MONTH

After all that time you finally collect your hundred smackaroos6!

THE FORECAST

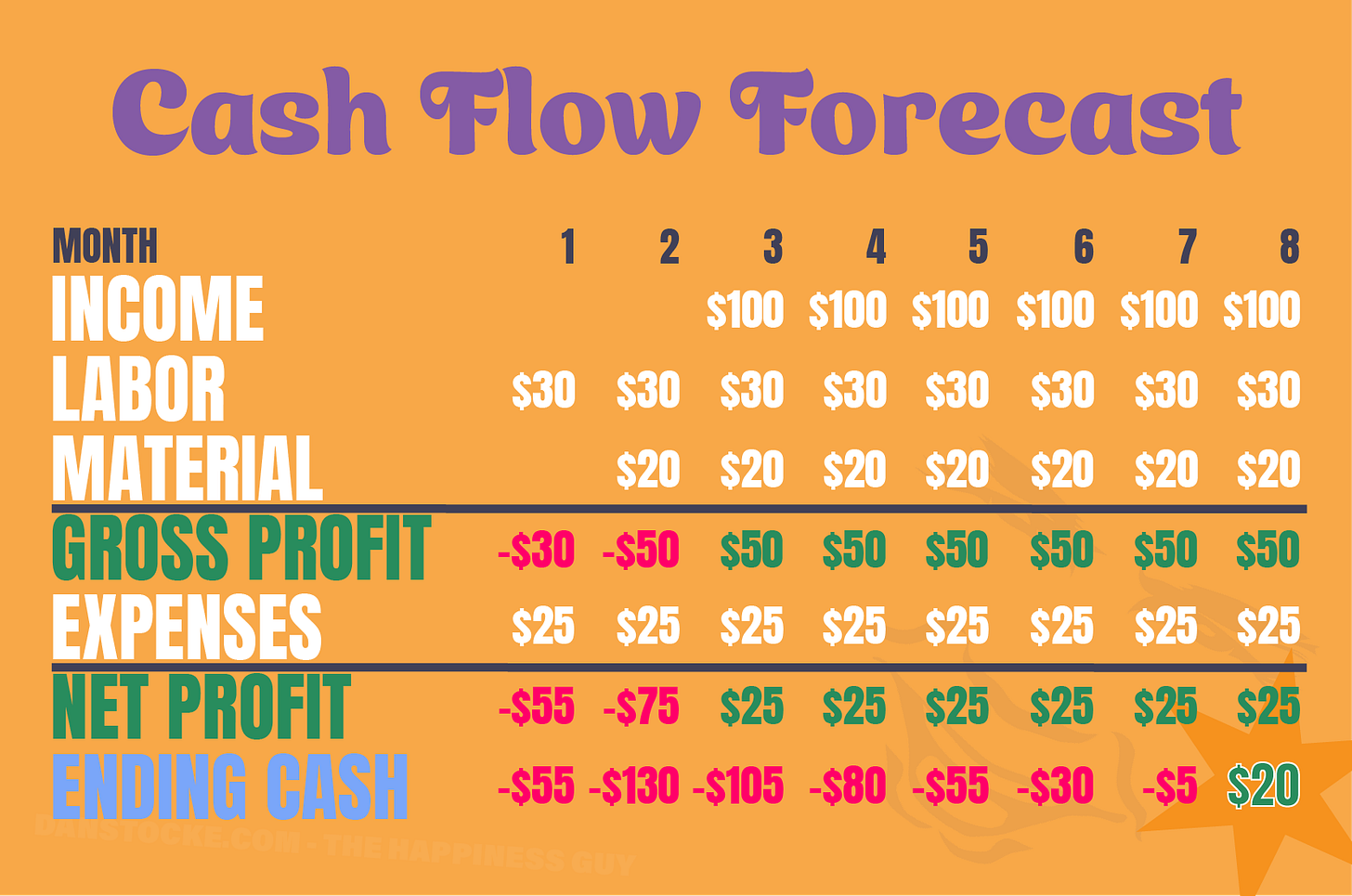

That’s a long way to go to make $25, but keep in mind: we’re in business. What we have here is known as an “ongoing concern”. We have to do this every month. We need to take this whole “when-we-pay and when-we-get-paid” thing and play it out over time.

Fuck!

According to this little spreadsheet, if we keep this up, we’ll lose $55 in the first month, lose another $75 in the second month, and only make $25 in the third month. If my math is correct, we’ve lost *taps on calculator* $105! WE’RE LOSING OUR ASS OVER HERE!

Not so fast, Chicken Little. We just need to push the forecast out a little further. We’re also going to add one more line:

Ending Cash: This line tallies up what we’ve made (or lost) so far.

It takes 8 months to get to a positive number in the ending cash:

You’re probably thinking that it took a long time just to make 20 bucks. But after month 8 we’re adding another $25 a month. And multiply those numbers by a thousand or a million (or a billion) and you begin to understand that it might be worth the wait.

Once again, this is a very base level Cash Flow Forecast. In a future post I will show you what happens when a business grows (it’s good), when it grows too fast (it’s bad), and when it rides the ups and downs of a consistent business cycle7 (it’s good).

Now you have a basic understanding of the language of capitalism and, if you work for a small business, a better appreciation of why your boss has that look of confusion permanently etched across their face.

(TO BE CONTINUED)

If you don't know how to speak it, you'll never be able to change the language. If you want my take on it, read the article Fixing Capitalism Through GAAP.

When you’re counting every penny, this is where the pennies are.

I know, but this is a remedial class.

Consider this a two-for-one special.

What did you think that saying meant?

Sweet, sweet cash!

Like sales slowing down around the holidays (or vice-versa).